The last thylacine

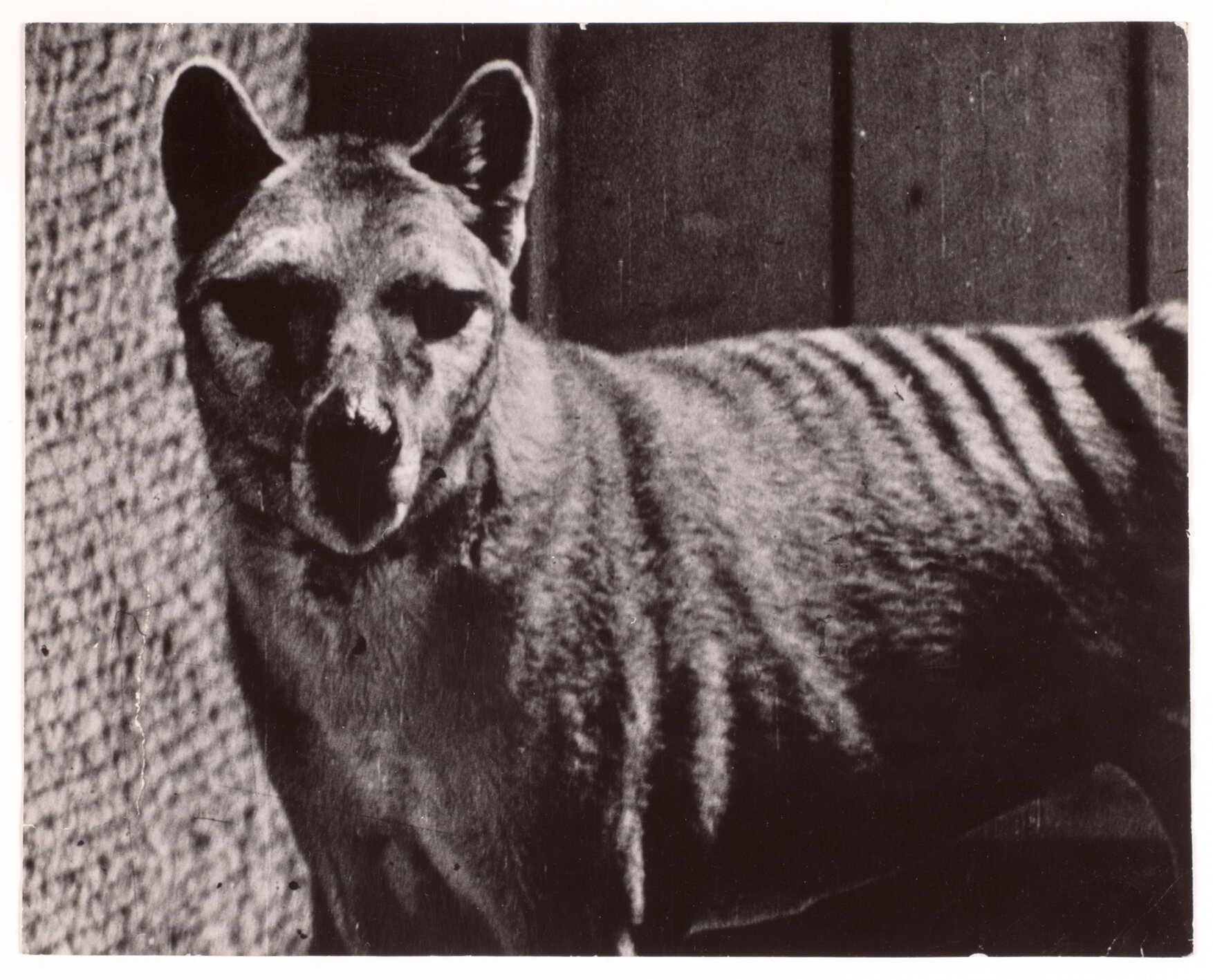

Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacine). Photograph AA193/1/1003 from the Archives Office of Tasmania,

is reproduced here, courtesy of the Libraries Tasmania Online Collection.

It has been a productive year for Tasmanian Tiger Archives researchers Brandon Holmes, Gareth Linnard and Mike Williams, who recently rediscovered moving images of the last known captive thylacine at Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo, in the National Film and Sound Archives.

‘Tasmania the Wonderland’, the 1935 travelogue by Sidney Cook, has reignited speculation into the origin and life history of the thylacine dubbed ‘Benjamin’.

Prior to the new discovery, Australian naturalist Dr David Fleay’s famous footage of Hobart Zoo curator Arthur Reid and a white terrier interacting with the last captive in 1933, had been considered the last film recording.

In the recording, Arthur Reid is shown using his unique ‘prodding’ motion on the fence to rouse the thylacine into action.

Fleay reflected in Memories of a Tasmanian Tiger, ‘Not long captured and still wearing the springer snare brand above his right hind leg, this long, lean softly padding animal had an ethereal appearance.’

And in the Australasian, ‘Late in 1933, during a visit to Hobart, I was fortunate in photographing the last marsupial wolf in captivity, and unfortunately, this fine male animal died not so many months later. It had been in Hobart for three years, at that time.’

The last captive can be identified by a distinct snare ring on a slightly elevated rear ankle, in addition to an anatomical comparison of the stripe pattern which is unique for each thylacine, as noted by Sleightholme and Campbell* in 2015.

Despite an end to the stock bounty scheme in 1909, the thylacine continued to be caught in ‘powerful springer snares’ set by trappers who were targeting wallabies and pademelons.

There are several theories regarding the source of Benjamin, including the long-held belief that the animal was captured by Elias Churchill at Tasmania’s Florentine Valley in 1933, however, there is no evidence to support this position and it has been dismissed.

Walter Mullins sold an adult female and three young cubs to the Hobart Zoo in 1924 and has been suggested as a possible source. However, the Mercury reported the last male cub died in April 1930.

Visitor testimonials describe an old, male thylacine that had been at the Zoo for many years.

Vita Brown described Ben as ‘very old, sad, lonely and pacing.’ She says she left and never returned.

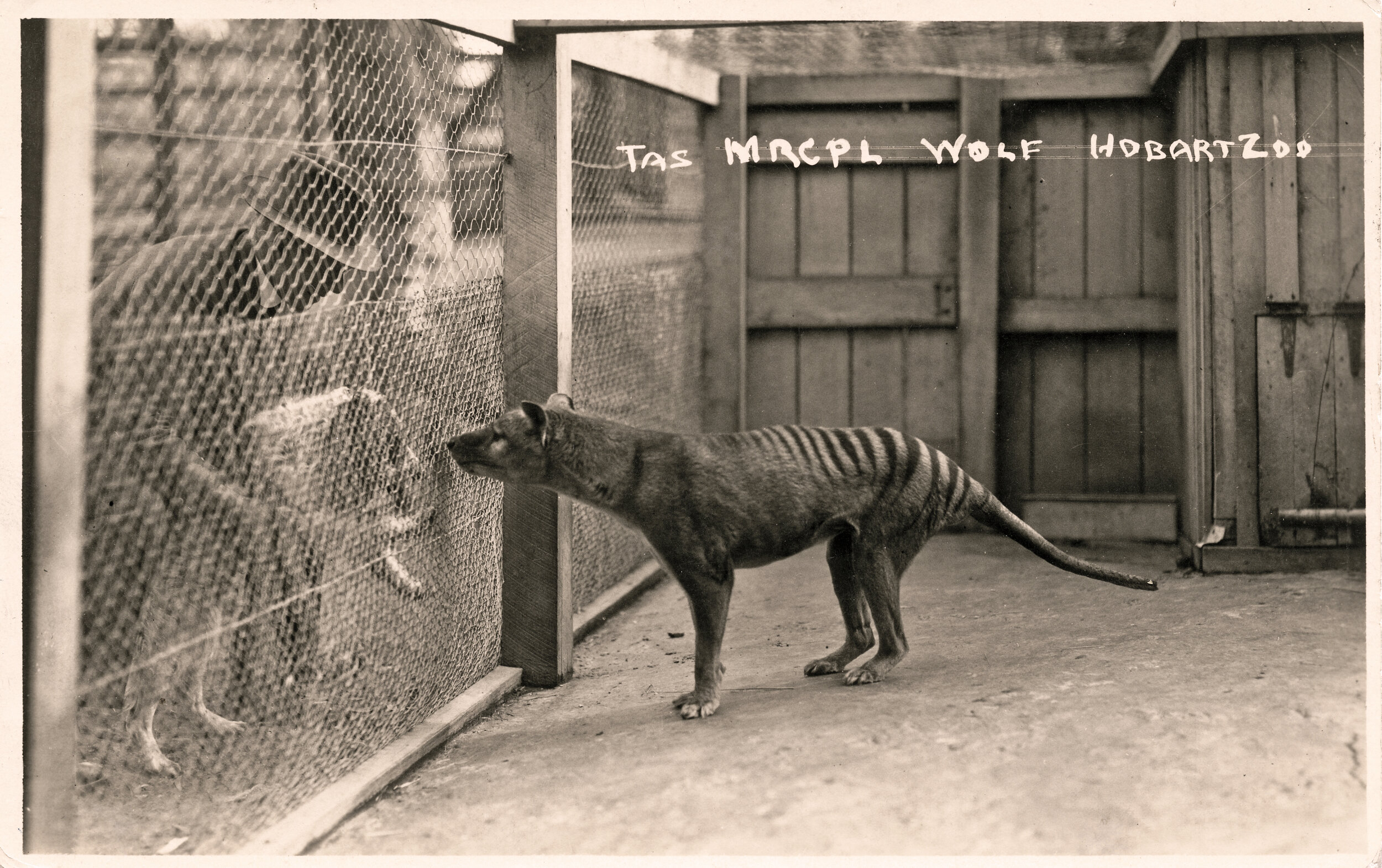

Gilbert P Whitley says he purchased a postcard at Hobart Zoo during a visit to Tasmania for a work conference in 1928. The postcard features Benjamin peering at Arthur Reid and an English setter.

Will Cramp on ABC Audio, ‘Used to help on Sundays. Got to know him over the years. Developed a real empathy with him. Bones, meaty bones. Paced in a not very big enclosure. Early morning call.’

Australia’s largest carnivorous marsupial, Tasmanian Thylacinus cynocephalus, also known as the tiger wolf, zebra wolf, marsupial wolf, hyena opossum, Tasmanian dingo, zebra opossum and dog-faced dasyurus, was added to the Tasmanian list of wholly protected animals on 10 July 1936.

The Hobart City Council Reserves Committee Minutes reported the last captive’s death on 16 September 1936.

‘The Superintendent of the Reserves Committee reported, “The Tasmanian Tiger died on Monday evening last, 7th instant and the body had been forwarded to the museum”.’

However, there is nothing recorded to prove the last thylacine ever arrived at the Tasmanian Museum in Hobart (TMAG), and Tasmania does not have an intact adult specimen registered in the International Thylacine Specimen Database.

The ITSD was initiated in 2005 by museums and universities to digitally photograph and catalogue all known thylacine material from around the globe.

Updated in 2017, the database includes three pouch young in the Tasmanian collection, in addition to three taxidermied mounts by the curator’s daughter Alison Reid. TMAG currently has the c. 1925 mount on display, while two female mounts, c. 1928, are in storage.

Miss Reid, who increasingly took on animal care duties at the Zoo said in 1992, ‘thylacines in poor condition were not offered as museum specimens, they were buried up on the bank at the zoo.’

In 1937, the Tasmanian Fauna Board expressed fears the ‘native tiger’ may have ceased to exist based on reliable data indicating it had been some years since the last tiger was seen in the state.

‘A letter has been sent to the Attorney-General advising that there were no specimens of the Tasmanian native tiger in captivity in the State at present, the single animal which had been in the Beaumaris Zoo for some eight years having died recently …’ (10 February 1937).

A lack of primary sources, erroneous dates and conflicting reports, places emphasis on the search for archival material and the essential role the Tasmanian Tiger Archives have in unravelling the life history of the thylacines held at Hobart Zoo between 1923 and 1937.

* ‘The earliest motion picture footage of the last captive thylacine?’, Stephen R Sleightholme and Cameron R Campbell, Australian Zoologist volume 37 (3), 2015

The postcard from Hobart Zoo, c. 1928, showing Benjamin peering at Arthur Reid and an English Setter. Photograph AMS597/66/1 is reproduced here, courtesy of the Australian Museum, Sydney NSW.